Originally appeared in Maximum Rocknroll #397 (June 2016).

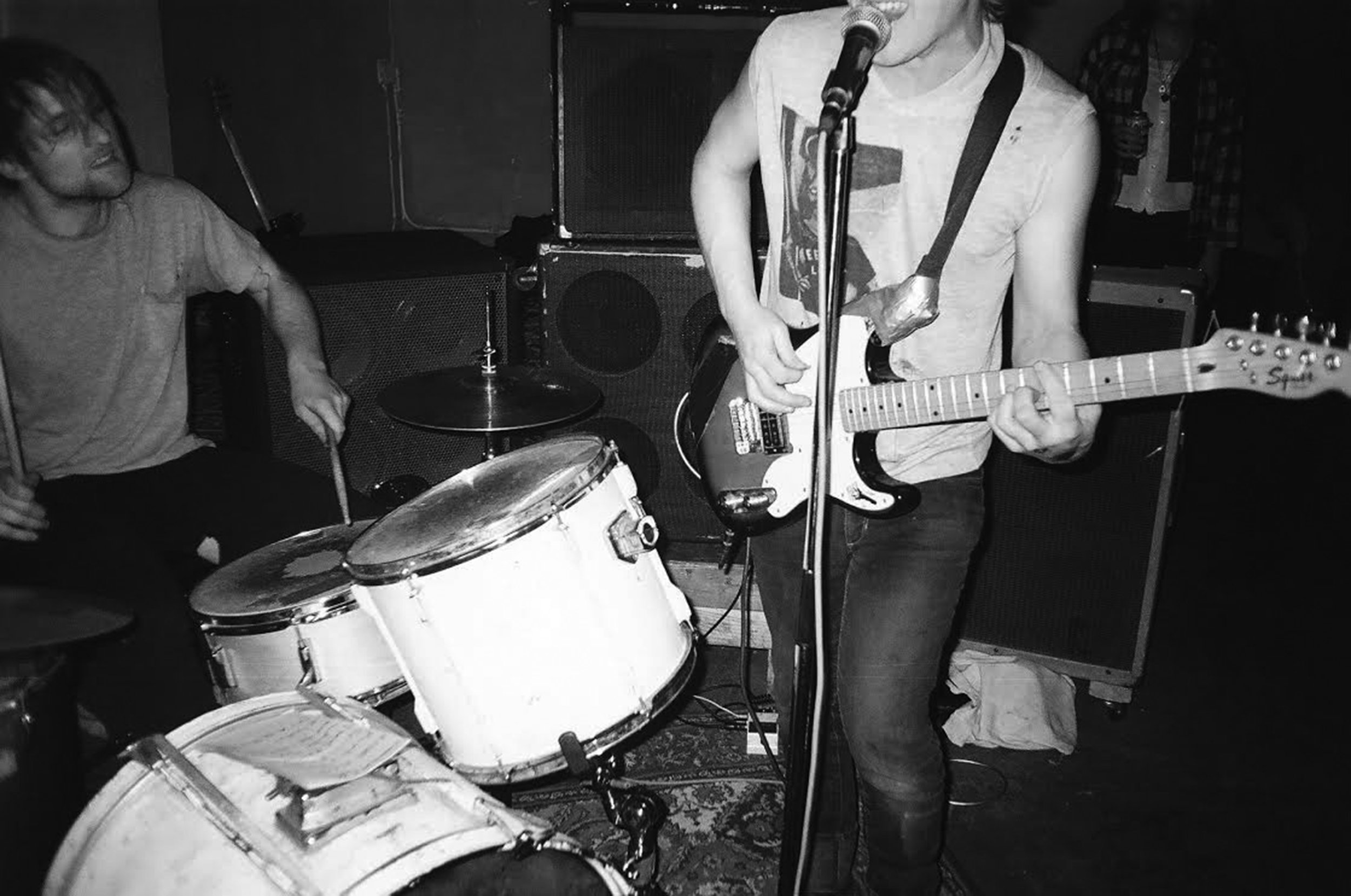

Portland’s Tiny Knives are one of the last holdouts from a powerful period in the city’s recent punk past. For me, they symbolize a time when you could go to a house show almost seven days a week and never see the same band twice. Growing out of the now-defunct Cook Street punk house, a onetime hub for art punks and bike punks alike, Tiny Knives has remained resilient while much of the scene they emerged from has been forced out by the city’s greed. In spite of this, Tiny Knives continues to put out song after song of rage and frustration. Their music, violent and cleansing, is an attack on everything this shitty oppressive world does to tear people apart and shut people down. It’s an emotional purge of the toxicities of this modern hell we call culture. On a recent trip back to Portland I sat down for a few drinks with guitarist and vocalist Jai Milx, bassist Ursula Morton, and drummer Jamey Anderson, to discuss their history and their newest record, Black Haze.

What brought the three of you together?

Jai: Jamey and I played a little bit of music together in a group that was at Cook Street. The group was Soo Koelbli from Big Black Cloud, Kitty Celeste, Adriane Ackerman, and a bunch of female people. We all played music together a couple times, and then nothing came of it. Ursula and I had talked about playing music like a year before. We talked about jamming on some stuff. I was in Popitilopitilus, but I wanted to play my own songs.

Ursula: Bob Jones, who was playing in Popitilopitilus, kept saying, “You should start a band with Jai,” and then I’d go and watch her and I’d be like, “Yeah, I’d really be into that.”

And Jamey was in the Vonneguts around this time?

Jai: Popitilopitilus and the Vonneguts had played together, and Jamey moved in around the corner so we were getting to know each other.

Jamey: We started hanging out a bit. Then I quit the Vonneguts, and was bandless for a while.

Jai: We were playing music in the summer with that project at Cook Street, but then when it got to winter I said to Captain Shirt, my partner at the time, “I just really want to start a band with people,” and he was like, “What about Jamey and Ursula?”

Ursula: I think Shirt and I met through Bob Jones too.

Was there a conscious decision to make Tiny Knives an all female band?

Ursula: Nope.

Jai: It was pretty circumstantial.

That’s interesting because when I lived in Portland that was the impression I got, and that seemed to be the emphasis.

Jai: I think that emphasis is put on us.

Jamey: For sure.

Jai: I understand that’s a point of interest and intersection with people who enjoy our music, and I enjoy seeing all female or queer bands. We actually were initially talking about adding other members, but it’s just that the three of us clicked so well, and we were making a full enough sound on our own.

Jamey: I had literally not met Ursula until the day we jammed.

Ursula: I had just seen Jamey play in the Vonneguts.

Is there a backstory to the name Tiny Knives?

Jamey: We were sitting at the Florida Room, trying our damnedest to come up with something. We came up with a few that were already taken. We were coming up with some that were terrible, like an-animal-plus-something-else bullshit.

Ursula: I was really into Hawk Moth. It ended up being a metal band from Australia or something.

Jamey: Yeah, we couldn’t do it. Any time we’d come up with something cool we’d Google it and find there’d already be a band named that. Like Mirror Mirror was probably my favorite band name. Eventually, I suggested Tiny Knives because I’m a knife nerd, and I’ve had a tiny knives collection for quite awhile.

Jai: I think it was partially inspired by Jamey’s tattoo too. Because Jamey has a little knife tattooed behind her ear.

Ursula: Jamey has a stick and poke that she had long before we were a band. Now we all have tiny knife tattoos that are from a more detailed, ornate, drawing that Jai did with fancy jewels and everything. Jai and Jamey have it on their forearms and mine is on my foot.

I’ve always been a little hesitant about labeling Tiny Knives a riot grrl band. I feel like it’s really easy to label female punk bands that. How would you describe your band?

Jai: I’ve started to say we’re a heavy band. When we started I think punk and post-punk were both really comfortable labels for what we we’re doing, but as we’ve kept going we’ve incorporated more elements of metal, hardcore, and noise. I think Eolian, the label we’re on, inspired me to start using the word “heavy” because they’re self-described as heavy music. I’ve started to just say that too because I don’t want to say that we’re a “punk post-punk hardcore metal band.” (laughs)

Ursula: I actually like thrashy, sludgy punk. But not “punk metal.” (everyone laughs)

Can you list some of the music that has influenced you?

Jamey: I grew up on riot grrl and hip-hop in equal amounts. And soul.

Ursula: I’m from the Midwest, so I was really into Dow Jones and the Industrials, and 70s punk bands from the Midwest. But then one of my favorite bands has always been Mudhoney. When I was younger I was really into Slayer, Death, Cannibal Corpse, and all these heavy death metal bands.

Jai: I grew up really loving riot grrl. I discovered Kill Rock Stars when I was fifteen, and I was so pumped and ready to order stuff from them. That definitely was a huge early influence on me. I listen to soul, girl groups, and oldies. And I listen to a lot of R&B these days. But growing up I loved the 77 New York punk bands, the CBGB scene, Richard Hell, Television. Patti Smith was a huge influence. Those were some of the first punk bands that I got into. I loved them because they were so intelligent and irreverent at the same time. And a lot of the punk that was being made in the 90s when I was growing up, especially in upstate New York, was just bro-ey hardcore. I had no intersectionality with that whatsoever.

Ursula: I was also obsessed with a lot of Kill Rock Stars bands. Unwound was one of my favorite bands.

Jamey: Budgie from Siouxsie and the Banshees has always been an influence on me as a drummer. All of his tom work and other stuff that he does.

There’s been some talk about sexism within the Portland metal scene. Is that something you all have experienced?

Jamey: It’s in the music scene. It’s honestly probably less in the metal scene, especially as far as the folks from Eolian go. It’s just something you deal with.

Jai: We’ve been around long enough at this point that we’ve garnered a certain kind of respect. Sexism is definitely alive and well in this scene. It’s something you have to work at being comfortable and confident with because people are going to assume that you don’t know what you’re talking about. And that’s a real ass thing about being a female musician.

Jamey: It’s often sound guys. What the fuck is up with sound guys?

Jai: Sexism manifests itself in the fact that we are constantly being reminded about the reality of us being a female band.

Right, and that’s why I wasn’t sure about asking you a question like this.

Jai: It’s both positive and negative. People who are female, or queer, or trans, feel empowered and excited by us being an all female band, and empowered to make their own music. I feel so fortunate about that aspect of it. But the other side of it is that people come up to you after you perform and are like, “Whoa, you chicks rule. Like you totally slayed it.” Of course, in Portland we get that less. You can walk into a music store here and someone’s not going to treat you like an idiot.

Jamey: After we get done playing there’s bewildered surprise from dudes that would have judged us.

Ursula: I tend to be kind of quiet and mysterious or something, and then after shows I get that, but I don’t think it has to do with my gender so much as just my personality. I always get people coming up to me after they saw us for the first time, and going “Wow! You guys shred.”

Jai: I have to say, I don’t think male vocalists get bros coming up to them after a show and being like, “That was so raw and vulnerable!” I don’t think that happens to male front people. At our last show at the Kenton Club three different men came up to me and told me, with slight variations of the words, that I was raw and vulnerable. I don’t think that happens to “Vlad” from some black metal group. No one says to him, “Man, that was so deep and I just go this impression of you as a vulnerable human being,” and then hugs them. I don’t think that’s happens to male vocalists.

Why did it take four years to release this album?

Jai: Originally when we started the band I was bringing a lot of the material, and then we’d finish writing the songs together. I’d have the basic construct of the song. Usually, I’d write the words first, and because I was just getting started I’d write them on acoustic guitar, then transfer to electric. Over time, and throughout our album Static, Ursula started bringing more and more ideas, riffs, and concepts. With this album Ursula actually generated the bulk of two of the songs, “Winter” and “Dark History.”

Jamey: Those are songs that Ursula brought to the table.

Jai: And she created the framework and had them pretty much done as far as her part went. We barely tinkered with the structure of those, really.

Jamey: We didn’t have to because they were so awesome and complex already.

Ursula: We’d add parts to them. Jai would come up with like a shell of a song, and we’ll add a bunch of stuff to it. And Jamey’s really good with song structure. But mostly I add the weird parts to everything.

Jai: This album was like pulling teeth for me. I was having trouble coming up with words. I was feeling really creatively blocked immediately after Static came out. And so the progress was really slow. In fact, we finished recording this album a year and a half ago, and then there were a bunch of stumbling blocks.

Ursula: It took awhile just to get together the artwork. And I think a lot of it is we usually play so many shows. This is the longest we’ve gone without playing a show — this period right now. Usually, we’re playing so many shows. We’re practicing our songs for our shows, and then not having enough time to work on new songs.

Does it come with just being active in life?

Jamey: I think for Ursula and I maybe more so.

Ursula: We work a lot. And Jai travels a lot too.

Jai: I’m out of town for two or three months out of the year.

Ursula: We already do have like four new songs.

Jai: We have two new songs written, and two others that are well on their way.

Ursula: We have a new song that is kind of like, not a concept, but…

Jai: A medley. We’re trying to write a multipart song, that’s like a journey.

Jamey: It’s going to be EP length.

Ursula: Like four songs that can stand alone, but that are all one song also.

Jai: And linked thematically. The theme is gentrification.

Jamey: Which is appropriate for fucking Portland.

How did you get involved with Eolian?

Jai: Josh from Eolian came up to both Ursula and I separately. He talked to us about really liking our band, and that he was interested in putting out a record. This was very early in the days of him taking over Eolian. He hit the ground running. He’s put out several dozen releases in the recent past.

The way I see it, Eolian is taking on every Portland band I still like.

Jai: They get described a lot in reviews of the label and the bands and stuff, including in one of our reviews, as weird, heavy music.

Jamey: Which is appropriate.

Jai: They’re open to non-conforming heavy music.

Jamey: It’s nice to have someone with distribution and contacts with promotion.

Who recorded the album?

Jamey: Caravan Recording. It’s Andrew Grosse and Jose De Lara, but Andrew mostly did the recording, and Jose did the mastering and mixing.

Is this Andrew and Jose’s portable recording service?

Jai: Yeah, but we did it in a space that Andrew had at the time.

Ursula: The idea of the portable recording is that they can go anywhere. For example, they recorded Oro Azoro in a church. The idea is that they can be mobile if you want to record in your bathroom or your practice space or whatever. But they also have a studio.

Jai: With isolation.

Jamey: Which they have for bands that just want to come to them, like us. And it was awesome. I mean we’ve worked with Jose on every single album we’ve put out, and have been happy every time.

Jai: He mastered the first album and was instrumental in recording the other two.

Jamey: Jose paired with Andrew was really amazing, because Andrew had some really good ideas about how to mic the drums.

The first song on the album, “Dark History,” is very guttural. It has an almost metal sound to it. The vocals are like something you’d hear on a grindcore record. Is this a new direction for Tiny Knives?

Jamey: It’s a progression.

Jai: I feel in some ways we have gotten heavier. For me, it’s in experimenting with singing, and with delivering in a guttural, intensely unpretty way. I laughingly call it my Cookie Monster vocals. I think a lot of my interests in the beginning laid with the rock ’n’ roll side of punk, and I didn’t know how to play metal, or grindcore, or other things, but as my musicality has improved I want to experiment. And I think that was intentionally a direction I went in with my vocals, and I’m not even sure that I’ll continue. I want to keep doing different things, and constantly be incorporating different kinds of music. That’s just how I am. I like to write in a lot of different veins.

Jamey: One of the things I love about this band is it’s always progressing, and changing in the best possible way. I’m never bored when we’re writing songs.

The cover of Black Haze is really strikingly different from the other covers. I mean, it’s really intense. You have these huge swords.

Ursula: The great sword was a Christmas present from me to Jose, and the short sword was a birthday present to me from Jose. The other sword we borrowed from our friend Arolia’s son, Dagon.

Jai: Eolian offered us the services of their photographer, James Rexroad. He’s a photojournalist. He took amazing pictures of when the conflict in Serbia was happening. He’s actually notorious, and bankrolled his life for a long time because he took a picture of Kurt Cobain’s dead body in Seattle. It was iconic and printed all over the place. So, we had the opportunity to take these pictures. The whole thing was my idea. I wanted to make a departure, something that was very much about us, and where we are at right now. I wanted to concretely tell someone this is who we are before they even listened to the music.

The previous albums, while they had their heavy moments, always had their lighter rock moments. Was there a conscious intent to make this album more cohesive in its sound?

Jai: No, but I’m glad to hear it.

Ursula: “The Fuck” is kind of like a more experimental, noisy song.

Jamey: I don’t know, “Silk In The Water” is pretty rock.

Ursula: “Past Tense” is a little more punk than the other songs.

Jai: Well, it’s got a post-punk feel to it.

Ursula: I mean, we can do that, where it kind of depends on who we are playing with. If we’re playing with a bunch of heavy bands, we can just play a bunch of heavy songs. And if we are playing with more punk bands we can play our less heavy songs.

Jai: I think that people expect that we are going to continually jump around with styles, but we are constantly working towards making a sound. One thing is that my gear has gotten a lot better. Ursula and Jamey’s gear has always been great, but I finally could afford to get a decent amp and some good pedals, instead of like the shitty $30 Metal Zone pedal I was using when we started. So I think as my gear has improved as well as all of our musicality has improved, we’re probably going to be more cohesive in our sound, but I think we’re never going to stop trying to branch out and do different things. I think this is a dark album though, largely because I was feeling really harsh, and really dark when we were writing it.

My favorite song on the new album is “Cowschwitz,” which has a kind of monologue in it that reminds me of something Crass would do. Can you talk a little bit about what inspired this song?

Jai: That’s actually the only song on the album where all the words were written before we wrote the song. We were on tour and in the van driving through that area that’s in-between San Francisco and Los Angeles, and there’s about two miles where there’s a bunch of beef lots. I’ve heard that they are for McDonald’s. But they’re terrible conditions. It’s just shit and mud. Before you get there you can smell it. You can smell it miles before. And every time you’re in a car, even if you roll up the windows and turn off the fan and—

Jamey: Roll up the windows!

Ursula: And in like 90 degree weather.

Jai: Yeah, in the summer time. That was the hottest tour ever. And we were driving through it, and I just got my notebook and I wrote every word of that song. No other song on the album came out that way.

The name “Cowschwitz” comes from a certain ranch, right?

Jai: See, “Cowschwitz” was something I’ve heard musicians in our scene in Portland refer to that area as. I was a vegetarian for thirteen years of my life. I eat meat now and I eat it regularly. But the idea of just creating such a shitty world for those animals and then putting it into your body is what inspired the song. At one point in the song I say, “humans create their own pain” and that’s like we are making this ugly fucking world and we are making it a part of ourselves, and that’s disgusting.

Jamey: I just learned this today, but schwitzen is “to sweat” in German, so it’s like cow sweat.

I thought it was in reference to Auschwitz.

Ursula: Yeah, that’s the idea.

Jai: I was a little concerned about naming it that, because I didn’t want it to be triggering to people in regards to the Holocaust. But it’s so much what that place is, and it’s such an iconic name for that terrible place. That’s what it’s called and I couldn’t change it.

Ursula: I mean, we all eat meat, and we try to eat conscientiously. I was vegetarian for ten years mainly because places like this exist.

“Cowschwitz” is kind of about suffering and pain but it’s a political song. A lot of your earlier songs are about personal suffering. Is there much of a difference for you between writing political or personal material?

Jai: Well, going back to the new stuff we’re working on about gentrification, I realized conversations I was having were about this issue daily. I went to Oakland for nine days, and every time I’d go to a party that’s the conversation I’d be having. I need to be putting this into my art. I need to be channeling this, because it’s destroying me. It’s paining me to watch other people’s struggles, and to experience my community being dispersed, and to be consistently affected by this menacing yuppie monstrosity. I identify as an anarchist and for me isolating the personal from the political experience is a very foolish road. My intersectionality with radicalism is about empathy. About being like: oh my god, these people are oppressed every day of their lives! People of color and queers, on a daily basis these people struggle in a very real way. Anyone who is like “I’m an oppressed person, I’m a woman, I’m queer, I’m a person of color, and I go out there on the street and I experience that every time I leave my house in some way.” To me that’s one of the most important things to the pathos of that, and trying to have relationships with other people in the face of that, both romantic and friendly and just in the world. It’s so difficult, and it carries so much weight. And to me there really is no separating the two.

When I listen to other bands who are political, and when I listen to musicians who are personal, they are usually one or the other, and there’s really few who can get that right in the middle, and I think you do that very well.

Jai: I think that holding an immense amount of anger over the world that we live in being so fucked is a giant driving force in why I make my music. It took me years to isolate and appreciate that anger, to actually acknowledge it for what it is. I didn’t want to be an angry mad person and, because I had a lot of self-esteem and depression issues, I was suppressing it and turning it against myself. Playing this music is incredibly cathartic to me because it allows me to channel other people’s and my own feelings of dysphoria and frustration with being in this world. It allows me to get it outside of my body in a very primal way. One of my new friends told me when he saw our band play this summer it was like watching an exorcism, and I was really flattered by that. In some ways I’m trying to make the space as safe as possible, and just clear that out of my system, and out of anyone’s system that wants to feel that and is listening.

Can you talk about “Silk In The Water”?

Jai: A lot of people don’t know this, but I also play pretty, acoustic music. And as we’ve been writing more guttural songs, to use your word from earlier, it’s been really challenging for me to play those songs, because my voice is gone half the time. “Silk In The Water” is a song that I wrote when I was maybe twenty-two years old. It was years and years ago. I wrote the basis of it, but it was a totally different song, and then Ursula and I went to work on it, hacked it into pieces, and then put it back together. That song was our albatross.

Jamey: We reworked it and reworked it and reworked it.

Jai: It was the hardest song on the album for us. We’ve done a lot of down tempo, prettier songs. “Ocean of Static Sky” on Static is a good example. That’s a very personal song, but “Silk In The Water” is more intentionally generalized. One of the central themes of that song is “I’m eating myself from the inside, and I’m corroding myself from inside” and the “Silk In The Water” name comes from a line that goes “silk in the water, dreams cannot keep their color.” There’s this idea that over time the world just wears people down and ruins them, and dissipates their most central identity and force. That’s loosely what I was talking about, but the lyrics are pretty oblique. But that’s personally where I was coming from when I originally wrote that song. And as we re-worked it, at the end I tried to make it a little more triumphant. The last words of the song are “decimate, let it rise.” It’s just trying to clear that and then allow health to come up from a ruined place.

I think culturally we usually don’t associate healing with violent, abrasive music.

Jai: We need to tear down innumerable things in our world to create a world where anyone can be a healthy person. And what I mean by healthy isn’t about eating kale everyday, but it’s about being a well-balanced person who isn’t carrying the ills of society as a sickness in their body. We have so much work to do as individuals and as a culture to even create a world where people can grow up and not be ruined by our culture. Everyone that I’m close with has suffered from being a person in this world in a very real and primal way.

Jamey: I think thinking about the way you’re interacting with the world, and how the world affects you, is fucking healthy. And Jai’s lyrics are helping people think about that.

Jai: I don’t know if they can hear them though. (laughs)

You also include two songs on Black Haze from your first album: “Magic Christians” and “Lights in the Sky.” Why re-record songs from four or five years ago?

Jai: I was the one who wanted to rewrite those songs. I had always felt like those two songs got the shaft in our first recording because “Magic Christians” was so guttural and predated our sound being dialed in, as far as being heavy goes. Our first album was a lot airier than this one.

Ursula: Also, I was going to say that we changed both of those songs. We revamped them.

Jai: And for “Magic Christians,” I just felt that song deserved a spotlight, because it’s a song that’s always been in our sets. We may not play it all the time, but we’ve revisited it and come back to it. And I felt that song needed some tweaking. I felt like it fit in with the other stuff we were playing, and we revamped it and reworked it and changed the middle pretty significantly. And I changed some of the things I was doing. As far as “Lights In The Sky” goes though, that was a song that dissatisfied me the most of all the songs we ever recorded. It was a slightly flubby recording. We went with the take even though it wasn’t the best. It was when we were first getting started.

Jamey: Was it the second song we ever recorded?

Jai: I wrote it years before I moved to Cook Street. It was the second song I brought to the band. The reason I wanted to revisit “Lights In The Sky” was because that song was about an experience I had being in an emotionally abusive relationship. It’s about being in Belgium and having an incredibly bad time, and being shouted at out on the street by this person. I wanted to revisit it because I thought that it was obvious to some extent from the lyrics what was going on, but I wanted to make it incredibly obvious, because I don’t think when people see me, or talk to me, or know me, they would expect I would have been in that kind of situation. I ended up writing this song and using it as a way to get past that experience and the trauma surrounding that. I was so dissatisfied with the recording, and I saw an opportunity to tweak the lyrics a little bit and make them more obvious. I added a number of lyrics but one of them that I added was “I know you’ve been abused, but it isn’t an excuse, you don’t know the way to break the cycle and change.” And so I wanted to revamp that song, and because I thought it was worthy of a better recording. I wanted to revisit that because I think abuse is a very real thing that a lot of people survive and struggle with. I experience PTSD from that relationship, and I wanted to make that incredibly obvious, and make it clear that is what the anger in the song is generating from, and what the desire for moving past and healing was generating from.

What’s the future for Tiny Knives?

Jamey: It’s kind of up to Jai. She’s threatening to move away.

Jai: I want to move somewhere I can buy a house, and that place is not Portland, Oregon. But I’m really stoked about writing this new cycle of songs. I keep joking about Abbey Road and the Paul McCartney songs, but I want to combine a bunch of songs into one sonic piece that are all really different and represent all of the different styles we have, but that are all recognizing oppression, and the way that is playing out around us. Calling out yuppies, of course, but also recognizing your own place in the web of gentrification.

Jamey: Yep.

Jai: And I feel incredibly passionate about that as a human being, and I feel really excited about working on that as a band.

Jamey: Me too.

Jai: That’s the immediate future, but long term future: we’re family, and I hope we play music together until we die.