In February I left the snowy streets of Brooklyn and traveled to Richmond, a city that’s been on my bucket list for years. Walking to the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, I saw a plaque on the street outside the museum that I mistook for a Toynbee tile. It was actually a Toynbee-inspired House of Hades tile. These mysterious tiles are found throughout the United States, somehow melted into the street in secrecy. I think it’s good luck to find one. The museum itself was small but well done. There was a Man Ray exhibit, but nothing I hadn’t seen. They had excellent pieces by de Kooning, Masson, Rothko, and a somewhat humorous one by Henri Rousseau. He embarrassingly has a Native American fighting a gorilla. I like the painting because it exposes Rousseau’s naivety towards non-European cultures. One piece that stood out for me and contrasted Rousseau’s obliviousness, was Jaune Quick-To-See Smith’s War-Torn Dress. This painting is of a Native dress in two panels. The top half, smeared in red, has the words “Your God” written on it, while the bottom half, covered in green, has the words “My God” written on it.

After the museum, I met with an old Portland friend, Nonnie, who now lives in Richmond. They took me to the fascinating Hollywood Cemetery, where Gwar frontman David Brockie is buried under a neo-medieval slab. Another plot had a cast-iron dog overlooking a child’s grave. The dog is said to come alive at night. There’s also a giant pyramid of blocks that seems to appear from out of nowhere. A complicated legend is attached to this cemetery. It’s said that the tomb of W.W. Pool was once home to a vampire. While I can’t do justice to the ins-and-outs of the legend, you can read about how the legend developed here. As it got darker, Nonnie and I walked to Belle Isle, a ruin-covered island in the James River. There were no lights and we walked the rough trail in the darkness. A thick fog covered the river and the rapids looked supernatural. Following this, Nonnie and their partner Katrina took me to Gwar Bar. The next morning, when I got on my train for Washington, DC, I rounded out the visit by listening to Gwar’s Scumdogs of the Universe.

DC was cold and wet. My first stop was the National Gallery’s modern wing, which was closed when I visited in 2016. Perhaps it was my mood, but I felt let down. They did have some nice work by surrealists Kay Sage, Tanguy, William Baziotes, Matta, and Magritte, not to mention Joan Miro’s famous The Farm. There was also one of those wonderful early works of Rothko’s that defy what people expect from a Rothko, and another work by Jaune Quick-To-See Smith. After checking into my hotel, I ventured out into the cold night to Meridian Hill Park where I saw the noseless and handless statue of Serenity, the most beat-up sculpture in the city.

In the morning, I made a trip to the Phillips Collection, where William Merritt Chase’s Hide and Seek made an impression. It was painted in 1888, my recurring number! After that, I went to the Hirshhorn. They had a rather lame Marcel Duchamp show, which was juxtaposed with a cool Laurie Anderson exhibit. In part of her exhibit, she projected human images onto little clay figurines, making them look alive. It reminded me of the Dr. Pretorius scene from The Bride of Frankenstein. I also learned about her Institutional Dream Series where she would try to sleep at different locations in New York to see if it would change her dreams. Next I visited the Smithsonian American Art Museum, which always has a slew of self-taught artists. Bessie Harvey’s Birthing shook me to the core. I followed that up with a trip to the Renwick Gallery which had a few interesting objects, such as a glass chandelier meant to look like it’s made from sausages. I had time to kill before my train to New York came, so I went to the natural history museum on a whim. They had some great objects, such as a square pumice deposit from Crater Lake, a small boulder of purple quartz, and an erotically suggestive double coconut.

In March I took a trip to Florida to see Edward Leedskalnin’s Coral Castle, a lifelong goal of mine. From my hotel in Miami Beach, it took three hours, two buses, two trains, and one rainstorm, to get to Coral Castle. The structure is mostly a square of coral walls, with coral furniture and household items of coral inside the walls. People like to dwell on the question of how Ed built the castle, but really it was just hard work over twenty-eight long years. I’m more interested in why he made this castle. Ed said he was building the castle for his long-lost love, but she seems to be just a myth. It feels like a tribute to the family Ed never had, where a man’s home is his castle. There’s some symbolism happening with the rocking chair, a motif repeated throughout the castle, but I don’t really know what it means. Something about Ed that doesn’t get mentioned is that he was good at repurposing old tools and items. Many of the tools he used to build Coral Castle came from old model T cars. Another thing that doesn’t get mentioned is that the entire place is engulfed with African rainbow lizards.

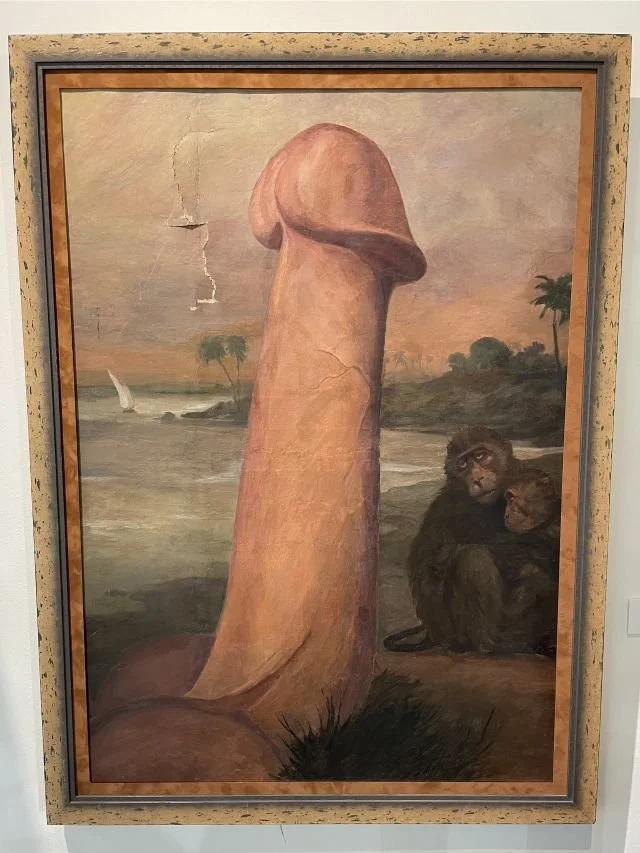

I’m not sure what to say about Miami Beach, but it was full of bare butts and alien-looking Banyan trees. Not far from my hotel was the Wilzig Erotic Art Museum. Although it’s a very lo-fi museum, it’s the best museum in Miami-Dade County. It’s full of penises of all sizes. One was about ten feet tall. There was also a wall of vaginas. A lot of the work was anonymous, but there were some works from major artists: Mose Tolliver, Hans Bellmer, Klimt, Schiele, Tom of Finland, and Milo Manara. One of my favorite pieces was a painting from the early twentieth century of a large penis growing out of the ground. Next to the penis were two monkeys shamefully looking at the penis. There was a puncture wound through the painting as if someone had once tried to destroy it. I went to The Bass next and discovered the work of Haitian Edouard Duval-Carrié. In one piece, he has a lifeboat with a carnivalesque cast of characters on it, and a humanoid tree seems to be magically directing the boat.

That evening I went to a punk and drag show at Las Rosas, and in the morning the first place I visited was the Pérez Art Museum. The Pérez disappointed me. It felt small and empty. But it did have an exhibit inspired by Breton’s concept of the object-poem, with works by John Giorno, Joseph Cornell, and Claude Cahun. Michael Richard’s Travel Kit was my favorite object-poem. I went to the Rubell after and was overwhelmed. It’s one of the better curated contemporary art museums. Throughout the museum were Yayoi Kusama’s silver balls, and the museum had two of her Infinity Rooms. All the big New York names were there: Basquiat, Wojnarowicz, Cindy Sherman, Richard Prince, and Keith Haring. Karon Davis had some interesting plaster cast sculptures. One has a woman coming out of the ground, as if to pull down the man in front of her. But it was Hernan Bas’s work that surprised me. Bas’s work seems to document the life of a teen boy as he exists in a psychedelic and sexualized fantasy terrain. Bas’s painting On the Jagged Shores intrigued me. It shows one boy with a flashlight, walking along a cliffside. His light is projected at a deer, but he is unable to see all the shadow men behind him making love. After the Rubell, I finished things off with a trip to the Institute of Contemporary Art to see Betye Saar’s Serious Moonlight show. Saar appears to be heavily influenced by Haitian culture. My favorite part was a boat full of rocks, with hands that reach out from the rocks. Shadowing the boat from below is a diagram of a slave ship.

In March I also went to the Outsider Art Fair in Manhattan. There were a lot of paintings with eyes on them. Claude Bolduc painted a picture of Jesus with an erection and an eye at the end of his penis. Then there was a pillow covered with eyes. Another booth surprised me by having the UFO photography of Billy Meier. Even if it’s fake, it’s still art, right? I saw a lot of work by well-known names too: Henry Darger, Daniel Johnston, Joe Coleman, Minnie Evans, Ionel Talpazan, and Augustin Lesage were all represented. My favorite piece was a part of a triptych at the Joshua Lowenfels booth. It’s the middle piece of three works collectively titled The Enigma Puzzle Paintings of Ginsberg. No one knows who this artist is, but the works are dated to the 1930s and are from San Francisco. The piece I liked had a fallen tree crashing on an outhouse. The outhouse has collapsed on its back, and a woman in a red dress is climbing out of the shit pit, apparently having fallen into it when the outhouse was tipped over.

At the Outsider Art Fair, I found out about Art Without Intent: The Found Object Show, which was held a few weeks later at a gallery on Rivington Street. There were a handful of dolls and human-shaped objects that had been weathered in haunting ways. Decay was a big part of the show. Other objects had things written on them that, when out of context, seemed strange, like a plate with the word “tongue” printed on it. My favorite piece was a series of old rubbery toys in the shape of African animals. They deflated over time, and a rhinoceros, elephant, and hippopotamus had all become as flat as a pancake.

That evening, after I went to the found object show, I saw Nick Cave perform at the Kings Theatre in Brooklyn. I’m partial to Cave’s work with The Birthday Party and his cynical albums of the 1990s. But it was still enjoyable to see him perform his newer songs, many of them awkwardly about God, love, and hope. He did perform “God Is In The House” which always gets a chuckle out of me. I spent much of the concert wondering how I can get a suit to fit me as well as Nick Cave’s suits fit him.

I’ve gone to many punk and noise shows these last two months. I saw the synth-punk band Girl Dick perform at Purgatory. I felt obligated to check them out after Kembra Pfahler recommended them in an interview. At times they reminded me of a trans-fronted version of The Screamers. I saw the goth-punk band Melissa perform at Trans-Pecos. Of all the bands in New York, I’ve seen this band the most. Their singer Jane Pain is also a writer and photographer. She has a website that I like very much. I went to a random house show and saw an all-female punk band named Witch Slap perform a cover of Black Flag’s “My War” and a fistfight broke out. I saw Austin Sley-Julian’s post-punk noise project Sunk Heaven twice. Sley-Julian uses a weird self-made noise-making device (the combination of some kind of flat tool with a flashlight and a contact mic) to create emotively reverberated sonic scrapes. And finally, I saw Gyna Bootleg perform with Tim Dahl and Tamio Shiraishi at TV Eye. This was my first time seeing Gyna Bootleg, whose vocalizations came off as feral and hyper-aggressive. The performance felt like a dress rehearsal for some kind of cathartic sacrifice or explosion.

After hearing about filmmaker Nick Zedd’s death, I decided to have a marathon of his films. His work can be hilarious, like the one where a little boy enters a giant woman’s pussy. Other times, they’re weird mash-ups, with scenes from porn films mixed with images of cops, or are reminiscent of Warhol’s screen tests, just profiling the people in the scene. I laughed out loud when I saw Greer Lankton dancing in The Bogus Man wearing her Dee Dee Lux Fat Suit. My favorite short film was The Wild World of Lydia Lunch. The title is ironic, as Lunch is anything but wild in this film. It starts with Lydia reading a letter she wrote to Zedd, trying to dissuade him from coming to London. We know he comes anyway because all the footage is of Lunch walking around London looking depressed and irritated. Once the saxophone music kicked in I realized I was watching a very personal piece. This is the most vulnerable I’ve seen Lunch. It's a portrait of her but painted through the eyes of unrequited love. Zedd’s feature film, War is Menstrual Envy, is the crown jewel of his oeuvres. In it, Zedd shows us his mastery of lo-fi effects and uses them to create an ethereal post-apocalyptic landscape. Watching Kembra Pfahler swim in front of a green screen seems campy at first, but becomes simultaneously otherworldly and erotic. And the unwrapping of the mummy-like burn victim, makes for an eerie finale, with Pfahler and Annie Sprinkle flanking him as they put him on display for the viewer’s prying eyes.

Surrealism also turns a century old this year but lives on because the antagonist of surrealism, that drive towards misery and repression, still exists. Because of this anniversary, the Paris group issued a critical statement on digital technology and social media. I've always had skepticism of digital art. When I encounter a “laptop musician” at a show, I feel less than enthused. I also think there's a big procedural difference between a digital collage and an analog one. Still, I’m not ready to throw technology out in one fell swoop. Apps powered by artificial intelligence and spam poetry do play with chance. It’s like pulling a lever on a slot machine. We can still find within them what Philip Lamantia called the touch of the Marvelous. I believe the negative feelings people have about these methods have more to do with their conservative notions of what it means to be an artist. It feels like the same battle Duchamp fought with his readymades. Personally, I believe art should be made with what’s available.

Lastly, the International Exhibition of Surrealism in Cairo has generated a lot of negative criticism. Unfortunately, it appears the organizers chose to have questionable sponsors, rather than doing it themselves. I can’t help but side with the critics. State and corporate sponsorships are antithetical to surrealism’s core values. It has been said that many Westerners are privileged. We don’t live in Egypt or know the circumstances there. It’s true, we don’t have the same struggles they have. But if you have to compromise your values to put on an art show, why have the show at all? I feel this will be a sore spot for years to come as it shows a fundamental difference in thinking. I do want to congratulate them on putting together the show, as any event is difficult to organize. And I would also like to salute the La Sirena group for admirably making the trip to Cairo, which seems like a huge undertaking considering the La Sirena members all live in England and the United States.

Music I’ve been listening to on the subway:

Menace Dement - Nanna

The Birthday Party - Live 1981-82

Billy Idol - Whiplash Smile

Melissa - Melissa EP

Nick Cave - Distant Sky (Live in Copenhagen)

Movies I’ve been watching:

Resurrect Dead: The Mystery of the Toynbee Tiles (Jon Foy, 2011)

Gas Food Lodging (Allison Anders, 1992)

King of New York (Abel Ferrara, 1990)

Leptirica (Đorđe Kadijević, 1973)

Love Rites (Walerian Borowczyk, 1987)