Originally appeared in Maximum Rocknroll #372 (May 2014).

I can’t help seeing Oakland’s Erin Allen as a sort of renaissance man. Established as a visual artist; Allen is also abundantly active as a musician. Most in the Bay Area would be familiar with him for his parts in such noise rock and art punk bands as Sisterfucker, Work, Child Pornography, and High Castle. I first crossed paths with Allen in the spring of 2013 when I was crashing on the couch at the Huffin House, where he lives. At that time he was just launching a new project, an abrasive two-piece punk band called Straight Crimes. Won over by the grit and the hopeful nihilism of the songs, I sat down with Allen to talk about Straight Crimes, and their new 7” record.

MRR: Where did the name Straight Crimes come from? What does it mean?

The name is old. It’s been around for a while. I came up with it when I went on tour with Child Pornography. Because people were having trouble with that name I came up with Straight Crimes.

MRR: As an alternative?

Kind of an alternative. But I had also made some music as Child Pornography, and put it all on a CD, and called that Straight Crimes. And I was pretty much playing that music for the tour. I was watching the TV show Cops while making the music, and I sampled from it heavily. And I swore not to watch Cops ever again after that (laughs). The name to me means the straight life is not void of criminality. It’s dealing with marriage and its dealing with things that are…

MRR: The straight life in a conformist sense?

Yeah, and I also just think the name is funny. I just chose to use it because I had been in bands with fucked up names, and I just thought this was more open-ended.

MRR: I remember you were telling me once that people thought Straight Crimes had to do with “straight” as opposed to “queer.”

Yeah, I got a lot of flack for it at first. Some shit happened on the internet (laughs). That shit happens, and it only happened one time, but yeah I got flack for it at first.

MRR: How would you define Straight Crimes? A friend of mine called it “garage rock,” and I don’t really see it that way. How do you see it?

Blues punk. I mean, I just try to write songs with a guitar, and I pay attention to what has been done before with other guitar music.

MRR: I see it more as a sort of stripped down punk rock.

Well, there are flourishes there. I guess what I do with the guitar sometimes, there’s all that twang thing that I do. I mean, I’m not offended by being called garage rock. Some people would be.

MRR: Are there any particular bands you were influenced by?

I think what formed me as a guitar player was being a bass player first. And then I got turned on to Arab On Radar, and that taught me how to play guitar. I feel like I steal a lot from the B52’s, because there are a lot of moves that they do that I totally rip off. That guy had like two or three strings, and I basically play the guitar like I have two or three strings, even though I have five. And the detuning came from wanting to sound like Arab On Radar and Pink and Brown. Pink and Brown was an old John Dwyer project from San Francisco. I guess in general, I listen to a lot of jazz literally all the time. Mainly Charles Mingus, Eric Dolphy, and Roland Kirk. Jazz and Elvis. Lots of Elvis. I am disappointed at the punk view of Elvis. People in the underground generally dismiss him. I don’t think you have to like his music, but to hate on Elvis in a conceptual manner comes from an uninformed and ignorant point of view.

MRR: It’s interesting that you started as a bass player, yet Straight Crimes has no bass player.

I guess I play all the bass parts on the guitar. I’ve been thinking about that a lot lately, especially now since I don’t have a drummer (laughs). It’s always been a question whether or not to get a bass player, to sound fuller or whatever. But the whole thing about having a bass player for the band, especially in its recent past when I still had a drummer, is that this person would be doing essentially what I’m doing, and I would be telling them what to do, and they would just be another face. And I’m fine with that because it would be cool to have another person there with us, because maybe the audience would get bored with looking at me, and then looking at the drummer, maybe they would need to have someone else to look at too? But then that’s all the bass player would be, and they would be this person that I’d be bossing around, and I don’t want to tell someone what to do. So that’s always just kind of made me nervous about having a bass player.

MRR: Are you going to go with the drum machine from here on out? Because you’ve had two drummers now, right?

Yeah, I mean, essentially both drummers—Mick Crosby and Brad Bingham—have just had to leave town for one reason or another. I have experience with a drum machine because of Child Pornography, so I just decided to go for it and try it out. And it’s working. I made some four-track recordings. That made me feel a little bit more confident about it. There’s going to be a handful of drummers helping me out. Thomas from Baus, and Steven from Processors, are going to help me out for a couple of gigs in March.

MRR: Didn’t you play drums in another band?

I’ve played drums in Sisterfucker, and I played drums in Work. And I also played drums in a band called Fuck You. Now I’m in Violence Creeps playing drums.

MRR: How did you transition from Child Pornography to Straight Crimes?

Well, Child Pornography is punk music. It’s keyboard music. I had a drum machine. It was blues punk too. It was like the Screamers. I mean, the Screamers were just playing their instrument. They weren’t playing arpeggios. They weren’t hooking up their keyboards to sequencers and shit. They were just playing their instruments, and that’s what we were doing.

MRR: Was it just transitioning from keyboard to guitar?

Yeah. I mean, I played guitar in Child Pornography, but then I stopped. And then I started playing guitar again because of my other band High Castle.

MRR: Let talk about your new 7” for a minute. You have a lot of songs. Why put these four particular songs on the 7”?

Because they were the best ones.

MRR: You think they’re the best ones?

Maybe, yeah. It was all about math. It was going to be a 12”, and then I thought that would be unwise because we aren’t going on tour or anything. We don’t have a van and we don’t have jobs. It just seemed more economical, because people don’t fucking buy records from bands here, they buy smaller things like tapes and 7”s.

MRR: What’s your favorite song on the 7”?

“Punch a Flower” is probably my favorite song, or “It’s a Shitty Night.” I chose those songs because they all seemed to have the same feeling. Like on the Wack Emcees tape, those songs are from the same recording session, but are more grindy, and more straightforward punk. These four are more like pop songs, something that someone would just want to sing along to.

MRR: I wouldn’t say “pop,” but the 7” is more melodic. And the tapes seem more noise rock, more gritty.

I would agree.

MRR: There’s a phrase from the song “Punch a Flower” about “wrathless abandon.” Do you think that pretty much sums up what you’re going for?

Yeah, I mean, that’s my worldview. I just write the songs and I don’t think of words until after writing the songs. I mean, they’re full of intent. “Punch a Flower” is a song about punk music, it’s about being disappointed with punk music while being a punk, or growing up with punk.

MRR: Is that why on the inside of the 7” jacket it says “punk is not a virtue”?

Definitely. It’s like, I want to be punk but I don’t know why I want to be punk. That’s my angle. That’s where I’m coming from. That’s why the words are what they are. The “punk is not a virtue” thing is something I came up with because some people who are punk lie, cheat, and steal. I mean, punk music is something that has been around for—when was the first Black Flag record, 1978?—and it’s now 2014, and punk was way before that record, and we keep doing it, and we do it for a reason. But we forget that we are ripping off rock n’ roll and jazz and blues. And people forget about all this stuff. So “punk is not a virtue” is about that. But it’s also about punks are shitty and stupid most of the time. I mean, um, I’m shitty and stupid (laughs).

MRR: Would you say that sums up your lyrics?

Yeah, yeah. And I like writing songs about God and shit.

MRR: Yeah, one of my favorite songs is called “Spiritual Nada.” It’s from one of the tapes.

I have a weird religious background. I grew up in a weird evangelical Buddhist shindig. I feel like I grew up with the same grammatical religious bullshit that everyone else grew up with if they grew up in a religious household. Every world event that is major and is affecting our lives is touched with religion. And so how could I not write about that. I just wrote a song about Heaven. (laughs)

MRR: So you have two cassettes?

The first cassette was with the first drummer, Brad Bingham, and some of those songs are on the next cassette. The first cassette also features a bass player that we got off of Craigslist. His name is Jeffry Ribz. I put out a Craigslist ad, and he answered it. He just jammed to the songs. But then he wasn’t really available for the next tape, and he just sent me a poem, and that’s why there’s that poem in the second cassette. I mean, the second tape is basically just what couldn’t make it on the 7”. It’s just from the same recording session. And side two is just a bunch of live jams.

MRR: I know you’re a painter. How is your visual work connected to your music? I mean, I can see you put a lot of work into the jacket of the 7”. I’m just trying to find a line between what you do visually and what you do musically.

The posters are the most direct thing I do that you can assign to my music. The poster series is influenced by the art of flyers, and protest language, and just, you know, attitude. I feel like it just makes sense for me to continue doing that. It’s from tour lingo, and conversations that I have with my friends, and lyrics of my songs or other bands lyrics. So that’s a direct connection right there. Not to say that isn’t in my other art, but for that poster series there’s always an exchange. And it’s always easy for them to be right there at a punk show to sling them or give them to friends.

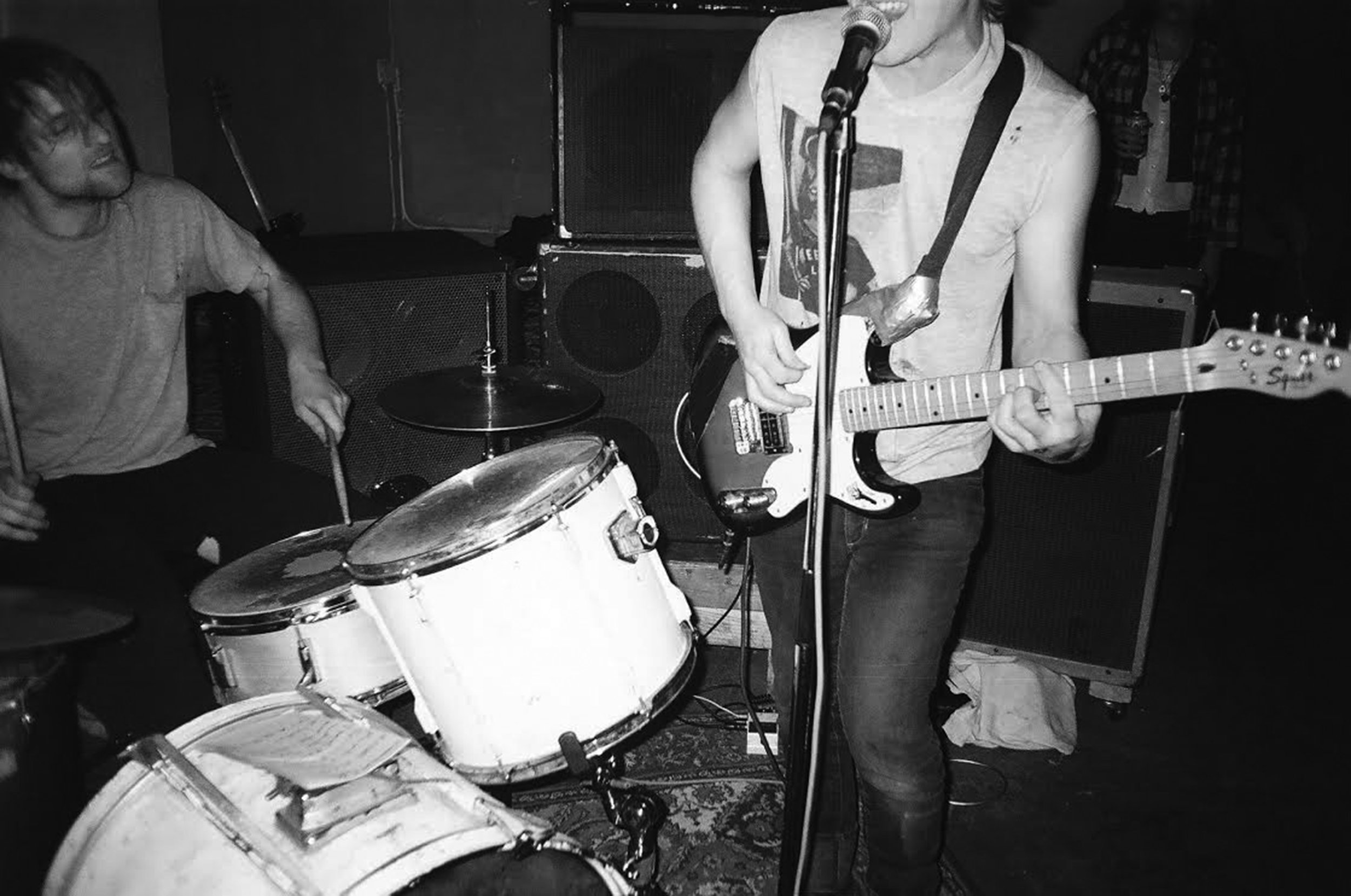

Photo: Kelby Vera

MRR: I find the use of the term “protest language” interesting. Do you think that influences your music at all?

Oh yeah definitely. I guess more in an utterance way, more in the way in which I sing.

MRR: The disconnect for me is that I understand your protesting, but I don’t know what you’re protesting. I don’t really hear Straight Crimes as a political band, yet there is something that you’re protesting.

I don’t want Straight Crimes to be a political band, but it is. What I want is for people to get a glimpse, get an idea, and then to form their own idea, form their own thoughts. I don’t ever want to give somebody an answer. I generally try to pose questions. But as of late I’m trying not to just pose questions, but also tell stories and be more narrative. But generally my attitude is to pose questions. I mean, that’s what the band name kind of is. Straight Crimes is kind of a question.

MRR: There’s a confrontation. But I feel like it’s in a more social way. Do you feel like art needs to be confrontational?

Generally, yeah. I participate in making confrontational imagery. That doesn’t sell, but that’s what’s remembered, and that’s what’s discussed. There’s all sort of art that is sold that is rich people’s wallpaper.

MRR: Some of your lyrics from “Punch a Flower” are “it’s easy to perceive, what you want to see/cough it up and call it blood it’s so simple to name it love.” What can you tell me about that?

Shit. I don’t know where that came from.

MRR: I think you’re talking about the phoniness of expression, in a way. It’s easy to put something out there are say, “this is my statement about the world.” But maybe there’s not always something behind that.

It’s hard for me to have a conversation about my lyrics, because my lyrics are pieced together. The way that I’m going to sing is pretty dictated by the music once the song is written. And I’m singing ad-lib, phonetically, making a mess of myself. And then lines work there way in. I guess that part in that song right there, well, I guess that first part is about High Castle breaking up. And the second part is about me falling out of love with somebody. All this different stuff happening. All these different things happening in different stages of when that song was existing.

MRR: Well, you talk about the breaking up of the band, and then the breaking up of a relationship. There are things that tie these words together.

Yeah, I don’t know if I can give you an answer. [laughs] For the most part, High Castle was a totally collaborative band. Maybe two songs I totally wrote, but the rest was just us jamming it out. “Punch a Flower” was one of the songs that I totally wrote for High Castle and we performed it at our last show. The lyrics were not fully developed at the time, or maybe rather, I changed some of the lines when I decided to do it as Straight Crimes. When High Castle broke up, it was weird because we kind of did it as a sit down, round table discussion. We just all agreed that we couldn’t write songs together anymore, but still wanted to be friends. I asked if I could still play “Punch a Flower” because I was already doing demos for Straight Crimes. Since I wrote the song and it was the direction I was going in, they said, “Yeah, but the High Castle version will always be better.”

MRR: I feel like your lyrics are really personal.

It’s funny, I really strive to write lyrics now, but you know when I was in Sisterfucker with Vanessa Harris half the time we were writing the lyrics right before we were going to record the vocals. And now she’s in Stillsuit where she sings, but she doesn’t have lyrics. They pretty much do what I do right before I write lyrics. (laughs) But they are steadfast, and they are sticking to it. I mean, it’s so weird, the pressure to write words. I definitely have the intention, but it’s weird that I would want to write the words, because most of the time you’re not going to fucking hear them at a fucking house show.

MRR: That’s just a way of being expressive, but keeping things hidden at the same time. Do you feel comfortable talking about your lyrics?

No, I don’t. (laughs) I wish words could be more heard at shows, but sometimes even because of the singing style, you just can’t understand the words. I can’t for the life of me understand what the fuck that guy in Sparks is singing about.

MRR: I want to get back to the music. I’m not a musician, but listening to the tapes many of your songs have a “marching” sound. I was trying to figure out where that comes from.

That comes from the Screamers, from bands like Crass. It comes from Sonic Youth’s more trotting rhythmic style. The “marching” feel I think is something that I’m very attracted to because there’s something about it that’s very protest-like, but celebratory at the same time. And also it’s like a dance beat too. Which is also like a lot of blues music that I listen to. I mean, I like making music that someone could move to. I started writing songs when I started fucking around with a drum machine. I guess that’s what has kind of informed me the most.

MRR: How do you see yourself, as the band Straight Crimes, relating to punk in Oakland? I guess what I’m trying to get at is that you’re really a solo artist, and that’s unusual. I mean, everyone is in a band.

I’m not by myself. The bands that I play with are writing those songs for me, basically. The friends that I have conversations with are writing the lyrics for me. I feel like I could be making this music with other people just as well as I’m making paintings with two other people. Collaboration is very natural to me.

MRR: So when you say they’re writing the songs for you do mean by knowing them, being exposed to them?

Yeah, what they do influences me. Nothing we do comes from nowhere. It comes from somewhere. And there’s so much different shit here in Oakland that can affect me, and it does. I don’t really feel alone. As far as the songs go, I might come up with a song and show it to a drummer, but what they do to it drastically changes it. And sometimes I change what I’m doing according to what they’re doing. Even though I’m acting alone I still feel like I’m participating with other people.

MRR: It’s interesting because I know the other project you’re involved in is a collaborative painting group, Club Paint. That’s a really curious contrast to you being in a band where you’re the only member.

Well, up to a few days a go I had another band member. (laughs)

MRR: But here you hold the reigns, so to speak.

There is always the person with the intent who is going to take charge… but I’m always open to input. (laughs)

MRR: How do you think it’s going to go tonight with just your drum machine?

Oh, it’s going to be the best show in the world. The only problem with the drum machine is that it can only be programmed for ten songs. Mick, the last drummer, he knew thirty-five songs!